How Dialogue Is Reshaping Transhumance in DR Congo

Raising awareness of Mbororo transhumant herders in Bili-Uélé, together with community leaders.

Across the Bili-Uélé landscape of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, elephants, chimpanzees, and other forest species share space with farming communities and the seasonal arrival of pastoralist herds.

It is a place where every movement tests the balance between livelihood and conservation. It is also here that Godefroid Azanga Mabutu moves with a different kind of urgency—the belief that seasonal livestock movement, known as transhumance, can be guided through agreement instead of confrontation as has long been the practice.

Conversations once defined by tension are steadily giving way to trust. What was avoided or raised only in times of crisis is increasingly being discussed early, openly, and collaboratively.

With stewardship by the African Wildlife Foundation and support from the European Union through the NaturAfrica Program, Bili-Uélé is demonstrating that peaceful coexistence can be built by design and grounded in dialogue and cultural understanding.

A Shared Landscape, a Shared Challenge

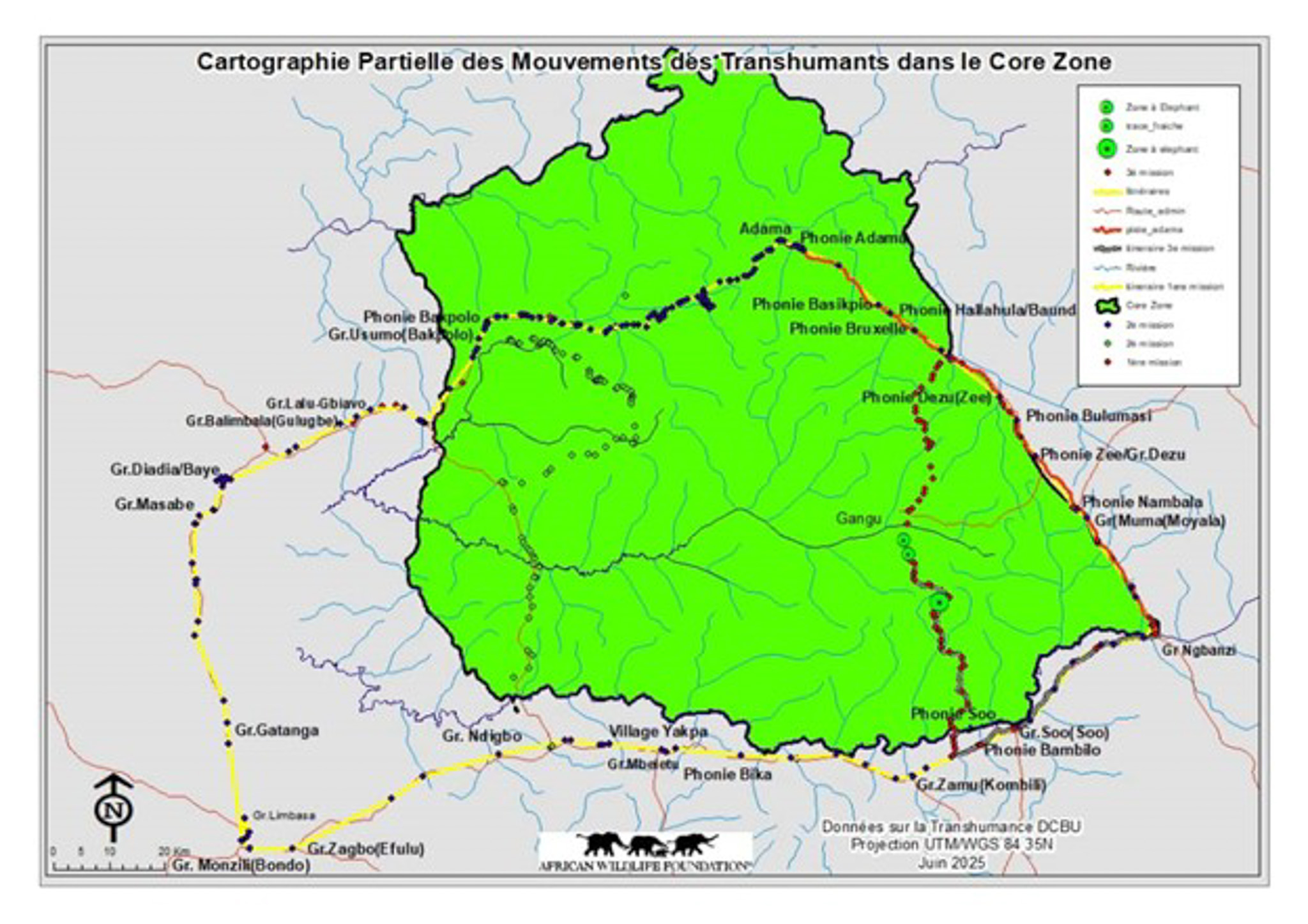

Partial mapping of transhumant movements in the core zone prior to raising awareness.

For many years, cross-border pastoralist movements disrupted wildlife habitats, strained relations with residents, and complicated conservation efforts. Farmers and herders struggled with the daily realities of competing needs. The ecological consequences were felt most sharply by wildlife and fragile ecosystems, as pressure mounted across key habitats.

Working alongside the Congolese Institute for Nature Conservation (ICCN), local communities, and pastoralist leaders, AWF is helping redefine transhumance as a shared responsibility: something to plan for, manage, and improve, rather than fear. The shift is both practical and relational, built through clear rules, consistent engagement, and a growing sense of co-ownership.

Godefroid Azanga Mabutu and the Discipline of Dialogue

At the center of this transformation stands Godefroid Azanga Mabutu, AWF’s Transhumance Agent. He is not just a facilitator; he is a bridge between pastoralist groups, ICCN officials, and community leaders. With deep knowledge of the Bondo Territory and its sociopolitical fabric, he navigates sensitive discussions with patience and clarity, helping each group see its role in protecting the landscape they all depend on.

"Transhumance is manageable when we agree," Godefroid says. "We need to engage in dialogue, raise awareness, and map out corridors to avoid conflict and protect wildlife."

His approach rests on two foundations: dialogue and sensitization. Through repeated engagement, respectful communication, and clear guidance, he helps ensure that herders understand protected-area boundaries, adopt sustainable practices, and participate actively in conservation. In practice, that means meeting people where they are, listening first, and then building workable commitments that can be upheld on the ground.

Raising awareness of transhumant herders in their savanna environment.

Building Trust With Communities and Mbororo Leaders

A critical pillar of the initiative is strengthening collaboration among all stakeholders, from Mbororo herders to village leaders and ICCN/AWF teams. Joint data collection conducted directly with herders, local communities, and conservation staff reinforces transparency and ensures that all voices contribute to managing pastoral movements. By gathering information together, stakeholders build mutual trust and create a shared understanding of the challenges and opportunities within the landscape.

Targeted communication further strengthens this foundation. The project team considers the social and ethnic structure of Mbororo clans so messages can move through the right channels and be delivered in ways that resonate culturally. This sensitivity to identity and clan dynamics reduces miscommunication and fosters constructive dialogue, which is essential for long-term stability.

Ardo Moussa, a respected Mbororo chief living in Bili, embodies this shift. After fleeing conflict in the Central African Republic, Ardo resettled in the DRC with his family and livestock. Sensitization sessions organized by AWF and ICCN were eye-opening, helping him understand protected-area limits, ecological fragility, and the long-term importance of wildlife.

"After these awareness campaigns, when we learned about the boundaries of the protected area, we agreed not to enter the restricted zone," Ardo says. "Conservation is important for us too."

Ardo’s leadership now extends beyond personal compliance. He encourages his community to respect conservation rules, teaches his children about wildlife protection, and advocates for services such as veterinary care and improved grazing resources. His involvement demonstrates how pastoralist voices, once perceived as adversarial, can become catalysts for ecological stewardship.

TANGO Teams, Visible Impact, and an African-Led Model to Celebrate

A discussion with the TANGO team after their selection by community leaders.

Progress has not come without obstacles. Seasonal migration still makes it difficult to reach all herders consistently, and securing the engagement of key decision-makers remains a challenge. Yet momentum continues to build, supported by community-based innovations like transhumance engagement officer (TANGO) teams.

These teams, composed of both residents and transhumant pastoralists, include women whose influence within families is crucial. TANGO teams are trained to communicate with empathy, avoid confrontation, and promote conservation-friendly practices in sensitive areas. Their presence models unity and cooperation, turning sensitization into a community norm rather than a top-down instruction.

"We must use simple, non-confrontational language," Godefroid insists. "Awareness-raising should never become a threat."

The impact of these efforts is increasingly visible. Conflicts between herders, protected-area managers, and farmers have begun to decline as all parties gain a clearer understanding of their roles, responsibilities, and shared interests. Awareness campaigns have helped both transhumant groups and local communities recognize harmful practices and adopt more sustainable behaviors.

Ecologically, sustained sensitization has encouraged pastoralists to gradually withdraw from the area's Hunting Reserve (DCBU) core zone, easing pressure on fragile ecosystems. As herders redirect their routes away from protected habitats, biodiversity gains a chance to recover and thrive. This shift is not accidental; it is the direct result of community-led dialogue and a deepening culture of co-responsibility.

What is taking place in Bili-Uélé is more than a local intervention; it is a model for African-led conservation. It proves that when people are respected, informed, and included, they do not resist conservation—they champion it. They become the protectors of the landscapes that sustain their lives, traditions, and futures.

A herd of transhumant cattle crossing the Bili-Uélé landscape.

"The road ahead will require persistence, resources, and political will. But the seeds of change have been planted," reflects Antoine Tabu, AWF’s Country Coordinator in the DRC. "With every conversation, every corridor mapped, and every TANGO team mobilized, [Bili-Uélé] moves closer to a future where wildlife roams freely, communities flourish, and conservation is truly African-led."

Across Bili-Uélé, dialogue is now doing what force and fear never could: aligning livelihoods with conservation, and turning a contested landscape into a shared achievement worth celebrating.